Ignacio Rodriguez Hurtado is a PhD student and Job Candidate at Duke University.

Click here for Ignacio’s job market paper Elevator Pitch.

In his prime, El Chapo Guzman led the powerful Sinaloa Cartel, raking in an estimated 3 billion USD annually. When asked why he began a life of crime, he remarked:

“The only way to have money to buy food, to survive, was to grow poppy, marijuana, and at 15, I began to cultivate it and to sell it.” El Chapo Guzman.

The quote highlights the connections between crime dropout_figure homicide_figureand the broader economy. Criminal organizations not only create violence but also draw disadvantaged youth into a life of crime. For many, the relevant choice is to stay in school and continue their education or leave school and join a life of crime. Criminal organizations, violence, and educational outcomes are intertwined.

This interdependence is the theme of my job market paper, which focuses on large Mexican Drug Trafficking Organizations (DTOs). I study the causal effects of the number of DTOs in Mexican municipalities on homicides and school dropout rates. As the number of DTOs increases, we expect crime to change as competition and criminal capital (criminal know-how and connections) increase, affecting homicides. Moreover, these DTOs frequently rely on adolescent males for labor, potentially affecting school dropout through labor demand. To illustrate the scale of DTOs’ labor demand, a recent article by Prieto-Curiel, Campedelli, and Hope in Science estimated that all DTOs combined are Mexico’s fifth largest employer. Studying the impacts of criminal organizations is an effective way to reduce both homicides and increase human capital, improving two critical outcomes for development.

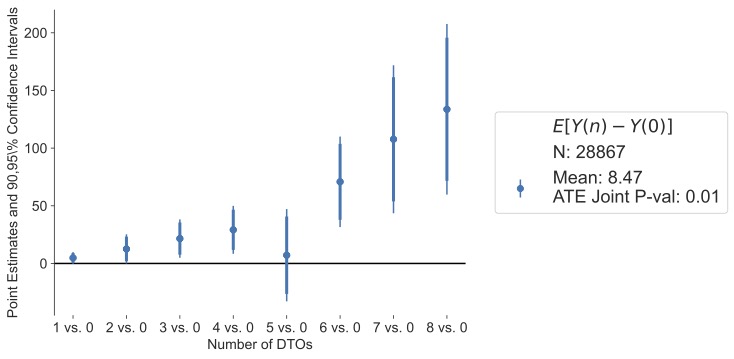

I estimate the average treatment effects of having 1 DTO vs 0, 2 DTOs vs 0, etc., on homicides and school dropout. Why do I estimate the full dose-response function of the number of DTOs? It can help inform policymakers. Ideally, crime agencies would deploy enough resources to eliminate all DTO presence. However, this policy is infeasible. A more realistic policy is reducing the number of DTOs by small increments, either by preventing an additional entrant or removing a marginal incumbent.

In this scenario, the shape of the DTO dose-response function is crucial for policy effectiveness. Suppose the curve between homicides and DTOs is increasing and convex, like an exponential curve. Then, reducing the number of DTOs in areas with many DTOs will result in disproportionate reductions in violence. Non-linearities in the dose-response function are policy-relevant. Thus, it is crucial to flexibly estimate multiple treatment effects to capture the non-linearities.

Data and Identification Strategy

The study uses data from Sobrino (2020) to track DTO presence. This data was created by crawling Google searches for news articles mentioning DTO names and locations. The data has been verified against US DEA reports and hand-collected datasets. I track the 8 largest DTOs between 2006 and 2020 across all ~2500 Mexican municipalities. I complement the DTO data with administrative data on school enrolment and homicides from the Mexican government.

I use instrumental variables combined with municipality-fixed effects to account for endogenous DTO entry, leveraging the rapid increase in DTO presence from 2006 to 2018. The instrumental variable is the one-year lagged distance from a DTO’s current operations to a potential new location. Simply put, DTOs like the Sinaloa Cartel consider how close they are to a target area and how close their rivals, such as Los Zetas, are before deciding to move into that area.

Reasons why lagged distance is a good instrument are summarized as follows:

- It has a strong first stage and passes the usual F-tests.

- After controlling for municipality-fixed effects, lagged distance is uncorrelated with several indicators of economic performance or the number of police officers in municipalities.

- Suggests instruments satisfy independence property.

- The exclusion restriction is plausible due to the limited potential of spatial spillovers.

- DTOs’ decentralized nature limits their capacity to shift manpower across the country or execute a long-term cross-regional expansion plan.

- Qualitative work suggests DTOs do not displace local criminals; instead, they either combat or subsume them entirely.

- I find no evidence for a migratory response.

- As a result, lagged distance affects outcomes only by changing DTO presence, allowing us to estimate causal effects.

I use the instrumental variables in a novel selection model in place of traditional two-stage-least-squares (2SLS) or difference-in-differences (DID) methods. I borrow from the industrial organization literature to model DTO entry as a dynamic firm-entry game, allowing forward-facing entry decisions. The selection model improves on DID or 2SLS:

- In contrast to DID, I allow for forward-looking entry decisions of DTOs, overcoming an important limitation of DID models.

- If DTOs make appropriate forward-looking entry decisions, then a parallel trends assumption would not hold.

- DTOs use their expectations to effectively select entry on the trend of outcomes select the trend of outcomes effectively.

- Traditional 2SLS methods fail when estimating multiple treatments.

- In contrast, my selection model delivers interpretable average treatment effects of having 1 DTO vs. 0, 2 DTOs vs. 0, etc.

How do DTOs affect homicides?

Below, I plot the main estimates for homicides. All regressions control for municipality-fixed effects and time-varying population counts to account for differences in municipalities.

Summarizing the results. I find an increasing and convex relationship between the number of DTOs and homicides. The effects of DTOs on homicides are staggering. For my sample, the overall average of homicides is 8.4 per municipality. Having 8 DTOs (the maximum number) causes an extra 133 homicides for the average municipality. However, I find even a single DTO causes a statistically significant increase in homicides of 4.7 extra homicides. So even a monopolist DTO can increase violence substantially.

The increasing convex relation I find has important implications for policy. Reducing DTOs where there are many, in the steeper part of the curve, will yield a larger drop in homicides than in places with fewer DTOs. These results suggest policy may be improved by accounting for the number of criminal groups and the market structure of crime more generally.

How do DTOs affect school dropout?

What do I find with school dropout? I find DTOs increase school dropout with a linear pattern, affecting males but not females in ninth grade. An additional DTO causes an extra 1-2 percentage point increase in dropout rates. Also, I don’t find any effects for younger grades. The overall average for ninth-grade dropout is 3%, so DTOs have a massive impact on school dropout.

The pattern of results suggests an opportunity cost channel, where DTOs offer attractive opportunities for male adolescents relative to schooling. I use centralized administrative data to confirm the results are not driven by outmigration. Consistent with this mechanism, I find that more DTOs result in higher numbers of teen crimes. Not only that, I find there are more teen crimes where the perpetrators are themselves a school dropout. So in summary, I find more DTOs increase school dropout and also teen crimes with offenders that dropped out of school.

This has a natural policy implication. Policies that reduce the cost of schooling would likely mitigate the dropout effects from cartels. This is because the dropout effects are driven by a labor demand channel. In turn, reducing the cost of schooling would also restrict cartels’ ability to recruit young workers, and commit further acts of violence.

Policy takeaways

Reducing DTO presence in areas with a large count of DTOs provides disproportionate reductions in homicides. Crime agencies should focus on areas with many DTOs to reap these benefits. However, areas with a small number of DTOs still have a substantial increase in homicides. As a result, if it is simpler to remove DTOs in areas with a few of them, the reductions in homicides would still be substantial.

Additionally, DTOs recruit male students through an opportunity cost channel. Policies that reduce schools’ opportunity costs, like cash transfers, may be effective in dampening the effects of DTOs. These policies would result in a “double blessing.” First, they boost human capital, fostering economic development. Second, DTOs’ recruitment abilities would be hampered, ultimately reducing the violence and crime they create.